(p. C1) ONE of the most influential political books of the last few years has been ”What’s the Matter With Kansas?” by Thomas Frank. Published during the 2004 campaign, it neatly captured the Republicans’ success in using social issues to attract blue-collar Kansans who don’t really benefit from Republican economic policies.

”All they have to show for their Republican loyalty,” Mr. Frank writes, ”are lower wages, more dangerous jobs, dirtier air, a new overlord class that comports itself like King Farouk,” and a culture in ”moral free fall.”

The book was a New York Times best seller for 35 weeks.

But close inspection uncovers a big problem with Mr. Frank’s economic analysis. Wages haven’t been falling in Kansas. Up and down the economic spectrum, they have been higher in the last few years than they were at any point in the 1980’s or 90’s, according to inflation-adjusted numbers from the Economic Policy Institute. The median Kansas worker made $13.43 an hour in 2004, 11 percent more than in 1979, which might help explain why many people don’t vote on bread-and-butter issues anymore.

Now, an 11 percent raise over the course of a generation — which is similar to the national increase — is (p. C10) not especially impressive. It’s certainly smaller than the increase workers received in the 25 years leading up to 1979, and for the last few years, wages have not risen at all. But they did rise during the 1990’s boom, and pretending otherwise does not jibe with most people’s experiences.

More to the point, some other improvements have accelerated recently. In just the last 15 years, the murder rate has been cut almost in half. Many big cities are far more vibrant places than they used to be. About 33 percent of young adults get a bachelor’s degree these days, up from 25 percent in the early 1990’s. The gap between men’s and women’s pay reached its lowest ever last year. The divorce rate has stopped rising.

Many luxuries of earlier generations — owning a three-bedroom house, flying across the country, calling relatives who live overseas — are staples of middle-class life. If all this doesn’t add up to a rise in living standards, I’m not sure what the phrase means.

For the full commentary, see:

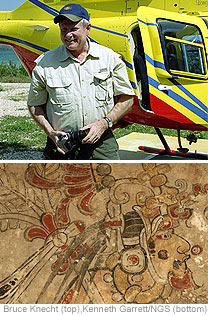

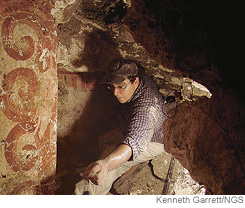

Upper left is retired banker Leon Reinhart. Lower right is Bill Saturno, who’s archeology dig is being funded by Reinhart. Source of photos: online version of WSJ article cited below.

Upper left is retired banker Leon Reinhart. Lower right is Bill Saturno, who’s archeology dig is being funded by Reinhart. Source of photos: online version of WSJ article cited below.

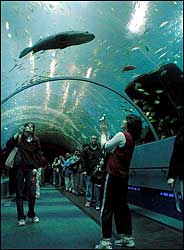

Scenes from the Georgia Aquarium. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited below.

Scenes from the Georgia Aquarium. Source of photos: online version of the NYT article cited below.

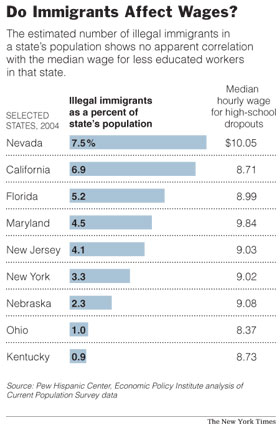

Source of graphic: online version of WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of WSJ article cited below. Source of graphic: online version of WSJ article cited below.

Source of graphic: online version of WSJ article cited below.